In late 1972, shortly after his twenty-seventh birthday, Lewis Baltz conducted an interview . . . with himself. The immediate spur for this unwonted act of self-inquiry is unclear, although it came at a moment when the artist was beginning to receive national attention for his photography. A typed transcript of the interview, which was never published, has recently surfaced, having been handed on at the time by Baltz to one of his students, Laurie Brown.1 Brown was then studying photography at Orange Coast College in Costa Mesa, California, and took a Beginning Photography class with Baltz. She subsequently wrote a short monograph about him as a final project for John Upton’s Aesthetics of Photography course. Brown recalls Baltz as a witty and exacting teacher, fond of brandy and cigarettes, driving students to match his own relentless dedication to the medium.2 Baltz had just begun to garner serious critical attention after his inclusion in Fred Parker’s exhibition The Crowded Vacancy: Three Los Angeles Photographers (1971), bringing together the new California landscape photography of Baltz, Anthony Hernandez, and Terry Wild.3

Baltz had just begun to garner serious critical attention after his inclusion in Fred Parker’s exhibition The Crowded Vacancy: Three Los Angeles Photographers (1971), bringing together the new California landscape photography of Baltz, Anthony Hernandez, and Terry Wild.3 Six months later, in November 1971, he received his first solo show on the East Coast at Castelli Graphics in New York—Antoinette and Leo Castelli’s inaugural exhibition by a photographer.4 The following year, supported by the curator, Thomas Barrow, he exhibited his series The Tract Houses alongside the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher at the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House.5

Six months later, in November 1971, he received his first solo show on the East Coast at Castelli Graphics in New York—Antoinette and Leo Castelli’s inaugural exhibition by a photographer.4 The following year, supported by the curator, Thomas Barrow, he exhibited his series The Tract Houses alongside the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher at the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House.5 All three exhibitions displayed work begun in the late 1960s: the series that became known as The Prototype Works (1967–1976), and The Tract Houses, made while he attended the Claremont Graduate School between 1969 and 1971. Centred on the mundane structures and alienating environments generated by California’s rapid post-war suburbanization, Baltz’s pointedly generic images initiated an intricate dialogue with American vanguard art and the legacies of photographic modernism.

All three exhibitions displayed work begun in the late 1960s: the series that became known as The Prototype Works (1967–1976), and The Tract Houses, made while he attended the Claremont Graduate School between 1969 and 1971. Centred on the mundane structures and alienating environments generated by California’s rapid post-war suburbanization, Baltz’s pointedly generic images initiated an intricate dialogue with American vanguard art and the legacies of photographic modernism. The self-interview came at a moment when the tyro artist was determinedly positioning himself beyond the circles of California photography that he felt had shown little understanding of his art. As Baltz later recalled of his time in Los Angeles, “I had a phenomenal amount of success early on, was dismissive and arrogant toward anyone I disagreed with, and was, I imagine, cordially detested by most of the photographic community.”6 Indeed, Baltz in dialogue with Baltz is nothing if not a polished work of self-definition. In a Socratic, if increasingly sardonic, exchange (it is surely written to be read, by his students perhaps?), the interview succinctly articulates the character of Baltz’s emerging practice. It describes his position within and against the world of photography, states his relation to the wider art “system,” and (with greater irony) comments on the photographer’s intellectual heritage and professional ambition. It also offers a sober gloss on the responsibilities of the artist to the wider culture.

The self-interview came at a moment when the tyro artist was determinedly positioning himself beyond the circles of California photography that he felt had shown little understanding of his art. As Baltz later recalled of his time in Los Angeles, “I had a phenomenal amount of success early on, was dismissive and arrogant toward anyone I disagreed with, and was, I imagine, cordially detested by most of the photographic community.”6 Indeed, Baltz in dialogue with Baltz is nothing if not a polished work of self-definition. In a Socratic, if increasingly sardonic, exchange (it is surely written to be read, by his students perhaps?), the interview succinctly articulates the character of Baltz’s emerging practice. It describes his position within and against the world of photography, states his relation to the wider art “system,” and (with greater irony) comments on the photographer’s intellectual heritage and professional ambition. It also offers a sober gloss on the responsibilities of the artist to the wider culture.

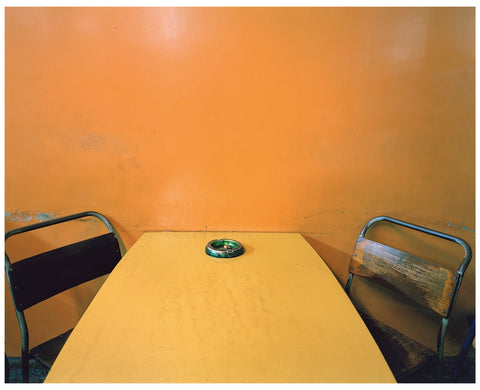

Above all, the interview reveals Baltz’s Greenbergian preoccupation with the definition of his medium, in particular the photograph’s framing (its “edge”), its shallow planarity, and carefully modulated surface, all of which direct attention to the beholding of the photo-graph. The photographer’s attention to flatness (although he never quite uses the term) places his discourse firmly within the orbit of mid-twentieth century modernist aesthetics in the United States. As the curator, Matthew Witkovsky, has argued, Baltz’s photography from this period amounts to a mode of “critical objecthood,” an effort to forge a “functional analog” to other forms of American vanguard art, specifically those associated with the contemporary minimalist, post-minimalist, and conceptual art movements. Indeed, Witkovsky cites the influence on Baltz of Ed Ruscha, Robert Morris, Richard Serra, Donald Judd, and Joseph Kosuth among a host of others.7 In the late 1960s, while still an undergraduate at the San Francisco Art Institute, Baltz pursued techniques that emphasized the medium specificity of his photographs. During the development of the negative and the production of the print he radically evened out the tonal contrasts of the image. He then glued the finished photograph to another piece of photographic paper, lending it a shallow protrusion on the mount, sometimes rimming it with India ink or raising it slightly with small diagonal incisions at the corners. The result was to draw attention to the photograph as both a three-dimensional object and a window on the world. As Witkovsky goes on to suggest, the luminous yet impenetrable surfaces of Baltz’s fastidiously crafted prints contrasted joltingly with the banality of his subject matter—the parking lots, commercial signage, and industrial facades, with their eerily featureless walls and windows, of California’s makeshift post-war architecture. Playing off the enhancement of photographic form against its function as transparent document, Baltz forged modernist photographs beyond compare. It was an avowedly avant-garde gambit, one that deferred to advanced artistic practice in the United States, all the while asserting his difference from the world of photography around him.

However, at the same time, as the interview makes clear, Baltz sees photography as “an art of content,” with a strong “documentary” connection to the world. Neither form nor content are privileged, but rather mediate an implicit tension, as he puts it, “between an inert, black-and-white, two-dimensional object, and an event that actually existed in the phenomenal world.” This is what the artist would later describe as his “double game,” an ideal conception of the modernist photograph as both informational image and autonomous work.8 For Baltz, the significance of this tension was very much of its moment. From the late 1960s, he was especially keen to distance himself from so-called “concerned” photography in the United States, an idea of documentary—photojournalistic, humanitarian, and anti-formalist—closely associated with Cornell Capa’s influence. Its power to command public attention seemed only to escalate as the nation became more deeply mired in the war in Vietnam.9

In a retrospect drafted during the early 1980s, and in the wake of the sustained avant-garde critique of documentary, Baltz castigated “concerned” photography for its epic failure. It was “the antithesis of effective social involvement,” he wrote, “a form of élitist play-acting, morally satisfying to the player, but without serious political or social consequence.” He continued:

If one wished to influence social or political issues, then images were no substitute for direct political struggle. Photography’s value lies elsewhere: in de-scribing the surfaces of the phenomenal world in a manner unique to itself; hoping, at best, to contribute a precise, if necessarily limited, understanding of the objects and events in front of the lens, and some insight into the mind behind it.10

Unduly quietist? Perhaps. Baltz’s formalism seemed even more pronounced in the heyday of Reagan and Thatcher. His own lack of “social involvement,” not to mention his canny self-positioning in the art world, routinely irked his more radical peers. For Allan Sekula (consistently Baltz’s most penetrating critic) the artist’s work was just too affiliated with the abstraction and ambiguity of painterly modernism, an unnecessary “separation of esthetic culture from the rest of life.”11 An instance of art photography, it constituted a “specialized sign system” referring either numbingly to itself or to other sign systems. But despite this, Sekula did feel compelled to concede the sensitivity of Baltz’s modernism to transformations in the social world, adding in a later version of his essay that it echoed “an ambiguity and loss of referentiality already present in the built environment.”12 In a post-revolutionary decade, Baltz pursued a muted historicity for the photograph, one, as Sekula pointed out, tragically devoid of human actors. Nonetheless, Baltz felt that the perceptual entanglement of form and content—a mode of veracity induced by the photographic document—was enough to stimulate the critical consciousness of his viewers.13

From 'An Interview with Lewis Baltz' by Duncan Forbes, published in September 2020.

Notes

1. The transcript surfaced in 2018 and is now among the Baltz archive and related ephemera held by the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

2. Conversation with Laurie Brown, April 30, 2018. Brown interviewed Baltz twice for her thesis, and he subsequently posted the self-interview to her. Baltz was also on the faculty of Pomona College, Claremont, at the time where he had recently completed his MFA. For a recent assessment of this period, including Brown’s landscape work, see Colin Westerbeck, Seismic Shift: Lewis Baltz, Joe Deal and California Landscape Photography, 1944–1984 (Riverside: University of California, Riverside and the California Museum of Photography, 2011).

3. The exhibition was shown at Memorial Union Art Gallery, University of California, Davis from April 5 to May 9, 1971, and Pasadena Art Museum from June 29 to August 29, 1971, before touring to the San Francisco Museum of Art, and the Friends of Photography, Carmel. Each artist was represented by twenty-five pieces. A small, accompanying catalogue contained nine photographs by Baltz, his first published work. See The Crowded Vacancy: Three Los Angeles Photo-graphers (Davis: Memorial Union Art Gallery, University of California, Davis, 1971).

4. The exhibition was staged between December 18, 1971 and January 15, 1972 at Castelli Graphics, Antoinette Castelli’s gallery at 4 East 77th Street. It comprised thirty-five prints made up of works from The Tract Houses and the series that later became known as The Prototype Works.

5. The exhibitions Bernd and Hilla Becher: Morphologies and Anonymous Sculptures and Tract Houses by Lewis Baltz ran from July 28 until September 17, 1972. Barrow would subsequently design Baltz’s first book, The New Industrial Parks Near Irvine, California (New York: Castelli Graphics, 1974).

6. Lewis Baltz, “Letter to g.w.s,” in The Collectible Moment: Catalogue of Photographs in the Norton Simon Museum, ed. Gloria Williams Sander (New Haven: Yale, 2006), 85.

7. Matthew Witkovsky, “Photography’s Objecthood,” in Lewis Baltz, The Prototype Works (Göttingen: Steidl, 2010), unpaginated.

8. See Matthew Witkovsky, “Oral History Interview with Lewis Baltz,” November 15–17, 2009, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

9. See especially Cornell Capa, ed., The Concerned Photographer (New York: Grossman, 1968), and Mitchel Levitas and Magnum Photos, America in Crisis (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1969).

10. Lewis Baltz, “American Photography in the 1970s: Too Old to Rock, Too Young to Die,” in American Images: Photography 1945–1980, ed. Peter Turner (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1985), 161.

11. Allan Sekula, “Postscript” to “School is a Factory” (1982), in Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photoworks, 1973–1983 (Halifax, Nova Scotia: Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1984), 234. For Baltz’s critique of Sekula, see “Burden & Sekula, poissons et sous-marins,” in L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui 312 (September 1997), 4–7.

12. See the version of “School is a Factory” in Allan Sekula: Performance Under Working Conditions, ed. Sabine Breitweiser (Vienna: Generali Foundation and Hatje Cantz, 2003), 251.

13. Baltz developed this point of view in relation to the work of Robert Adams, Anthony Hernandez, William Eggleston, and John Gossage in “KONSUMERTERROR: Late-Industrial Alienation,” Aperture 96 (Fall 1984), 4–7, 76. As he argued, photography’s “best vocation . . . is, as noted, subversion” (4). For more acerbic commentary on the status of the photographic document see the transcript of the question and answer session at the Symposion über Fotografie IV, Graz, 1982 published as “Lewis Baltz,” Camera Austria 11/12 (1983), 4–15.